Corner notches are the primary structural connection in a log home, so you inspect them first as load‑bearing joints, then as water/air barriers, and finally for settlement and decay.

Identify notch type and load path

Determine how the corners are supposed to work so you can judge what’s abnormal.

-

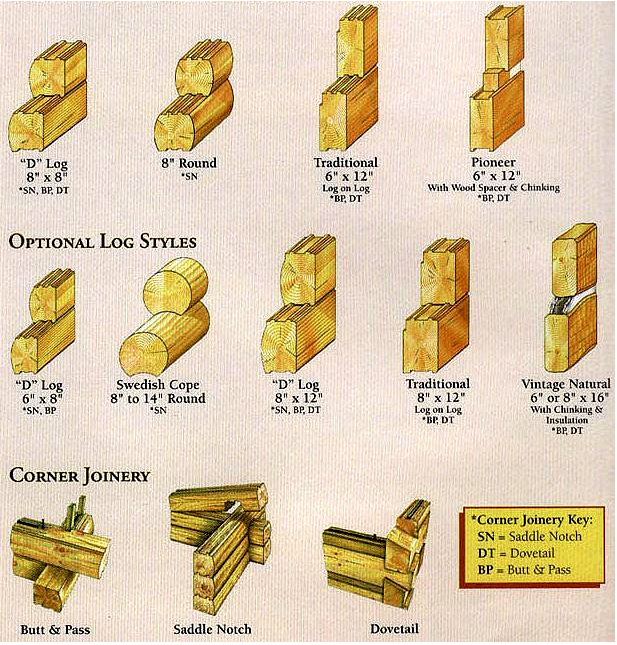

Note the joinery: saddle notch, dovetail (full or half), V‑notch/steeple, square, or butt‑and‑pass with fasteners.

-

Recognize that most of the wall’s structural integrity is concentrated at corners; significant damage, looseness, or decay here is a major concern.

-

Look for evidence of pins, rebar, or spikes that tie the stack together, especially on butt‑and‑pass or square‑notched systems.

Example: A half‑dovetail corner should appear tight and self‑locking; if the tails are visibly open or out of square, settlement or fastener failure is likely.

Exterior inspection of corners

Walk the exterior and inspect each corner from grade to eaves, using a ladder where safe.

-

Probe log ends and notches (ice pick/awl) for softness, deep penetration, or flaking, especially where runoff hits.

-

Look for checks and cracks oriented upward in the notch area that can hold water, discoloration, graying, or staining that suggests chronic moisture.

-

Check chinking/caulk at and between notches for cracking, gaps, pull‑away, or missing sealant that would allow air or moisture entry.

-

Observe any separation between intersecting logs at the corners, including visible daylight or irregular gaps that are wider at top or bottom (settlement indicators).

Document any heavily decayed log ends, crushed bearing surfaces, or open joints as significant defects and recommend log repair/restoration contractor evaluation.

Settlement and movement at corners

Corners often show settlement before straight wall runs.

-

Look for stepped gaps between courses concentrated near corners, or chinking compressed at some corners and stretched or torn at others.

-

Check for misaligned or racked corners where vertical joint lines are no longer plumb, indicating differential settlement or foundation movement.

-

Correlate corner conditions with global settling indicators: gaps between logs, sticking windows/doors, buckled trim, or separation at intersecting conventional walls.

If you see major loss of bearing at corners combined with interior distress (cracked finishes, misaligned openings), treat it as a potential structural concern.

Interior and air/moisture leakage at corners

Inspect interior corners where the log faces are exposed or where log walls meet interior partitions.

-

Look for visible light or air movement between logs at inside corners; note drafts, staining, or insect activity in these gaps.

-

Check for separation between log walls and intersecting conventional walls or ceilings, especially near corners where different materials settle differently.

-

Examine trim at inside corners and at fireplaces or masonry intersections for gaps and water stains, remembering that masonry does not settle like logs.

Interior evidence of daylight or air at corners combined with exterior joint separation supports a recommendation for resealing/chinking by a log‑home specialist.

Typical defects to call out and how to write them

Common corner‑notch issues that rise to “defect” level include:

-

Rot or advanced decay at log ends and notches (soft wood, deep probe, surface collapse).

-

Open or separated notch joints, visible gaps, or loss of bearing between intersecting logs.

-

Failed or missing chinking/sealant at corners, with air or moisture leakage evident.

-

Differential settlement at corners causing racking, misalignment, or distress in assemblies tied into those corners.